|

| What wines go off in your head like a light bulb? |

|

| Large-format bottles at Charlie Trotter's in Chicago. |

|

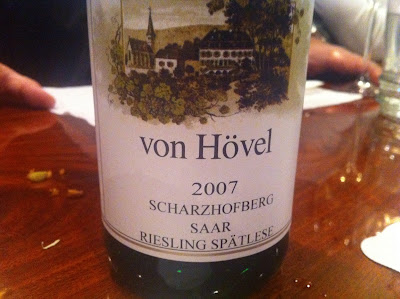

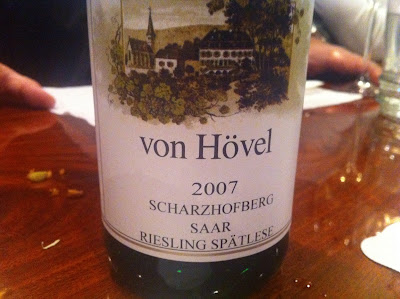

| Riesling at Lotus of Siam in Las Vegas is one of life's pure pleasures. |

|

| What wines go off in your head like a light bulb? |

|

| Large-format bottles at Charlie Trotter's in Chicago. |

|

| Riesling at Lotus of Siam in Las Vegas is one of life's pure pleasures. |

So where does that leave the question: How much is that wine in your glass worth? Probably never more than about $50. At that point, other factors start playing havoc with the amount you pay. Chief among those are prestige and scarcity. That is easily enough understood. There are roughly 500 cases of Domaine de la Romanee Conti's Romanee Conti made each vintage, centuries of legend behind the wine, and tens of thousands of people who would gladly pay to drink perhaps the greatest trophy among all wines. Put that all together, and you can grab a 750-milliliter bottle of 2009 Romanee Conti for $10,000 if you're lucky (almost $400 per ounce).

So where does that leave the question: How much is that wine in your glass worth? Probably never more than about $50. At that point, other factors start playing havoc with the amount you pay. Chief among those are prestige and scarcity. That is easily enough understood. There are roughly 500 cases of Domaine de la Romanee Conti's Romanee Conti made each vintage, centuries of legend behind the wine, and tens of thousands of people who would gladly pay to drink perhaps the greatest trophy among all wines. Put that all together, and you can grab a 750-milliliter bottle of 2009 Romanee Conti for $10,000 if you're lucky (almost $400 per ounce).

Hopefully by now you think wine is something you want to try. But a basic task remains: how do you drink it? That’s a stupid thing to ask, isn’t it? Open up and swallow it down. Well, it’s not quite that simple if you want to maximize the enjoyment of this wonderfully layered and complex beverage, but it doesn't have to be overly complex, either. Tony Soprano put it right during season five of The Sopranos when, after he uncorked a bottle of Dom Perignon to celebrate reconciling with Carmella, he scolded Anthony Junior for gulping it down like beer. “You gotta savor it,” he said. One thing that makes drinking wine such a pleasure, as with many things we enjoy in our lives, is the ritual that surrounds it. By no means should the ritual subordinate the actual pleasure of swilling it down, but a few small steps can maximize the experience.

Opening the bottle

You’ve done this before, but there are a couple tips to remember. First, your corkscrew makes a difference. Much like wine itself, they come in a lot of varieties, from the cheap to the ostentatiously expensive. The basic styles include the waiter’s corkscrew. These can be a challenge if you don’t have a lot of experience, since they don’t always go straight into the cork. There is also the “drill” type, which covers the top of the bottle and screws into the cork while a pair of arms raise into the air. Push the arms down, and the cork comes out. This is a great corkscrew, but make sure you get one where the tip that goes into the cork first is straight, not curved, or you can have the same problem as with the waiter’s corkscrew.

The easiest entry-level corkscrew to use is a Screw Pull. It’s also sometimes called a “rabbit” style wine opener. A good one will run you about $100, but it makes opening wine — young and old bottles — a breeze. You can also get a solid one for $20, but expect to replace it in a year or two.

Once the bottle’s open, do this: Smell the cork. A lot of people dismiss this as pretentious and unnecessary, a relic of past, unenlightened times — just the sort of thing it’s important to guard against. But the critics are dead wrong. Smell the cork. If it smells musty or like wet socks or mold, it is the first indicator that your bottle might have “cork taint,” which is what winos say when a chemical compound known as TCA, found in corks, ruins a wine. There are degrees of cork taint, and the cork is the first place where the off aromas will show up. Consider it the wine bottle's canary.

Last, pour a small amount of wine into your glass and take a taste. The wine may well need to have more contact with the air (called “opening up” or “aerating”) to fully develop its aromas and flavors, but the initial sip will let you know if the wine is flawed.

What kind of glass?

The key word here is “glass.” Fundamentally, you don’t need to worry about anything else other than drinking your wine out of a real glass. It doesn’t matter what shape it is. It’s just important not to be drinking out of plastic. You’re not going to basement keg parties anymore. (At least not to drink wine.) Down the road, you’ll want to invest in some inexpensive but good wine glasses. Target carries an excellent line of reasonably priced Riedel glasses. You should certainly consider three varieties: one for red wine, one for white wine, and a flute for champagne.

You want wine glasses to be clear — no color at all, without etching or cut glass. You want the lip of the glass to be thin, not thick and clumsy, which will negatively affect how you taste the wine. Other considerations change depending on the type of glass. For example, for red wines, use a large glass with a wide bowl. This allows you to swirl the wine in your glass and aerate it, making for a more aromatic bouquet (as winos call the aromas). For white wines, the glass is similar but smaller, without quite as large a bowl. Champagne flutes are probably old hat. But when you pick one out, simulate taking a sip to see if the tip of your nose hits the side of the glass. Many flutes these days are made with too narrow an opening on top, and if your nose makes contact, the oil will come off your skin, and that will inhibit the bubbles. What fun is champagne with no bubbles?

Pouring

This isn’t hard, but promise to keep one thing in mind: Don’t pour too much wine into each glass! Two or three ounces are plenty. This allows you to enjoy the wine and see how it develops as it has increasing contact with air. Many restaurants, if a party of four orders a bottle of wine, will empty it in one round of pours. What good is that? Pour in moderation, please. It’ll still be left in the bottle.

Drink up … but be sure to sniff first

Let’s be frank. Wine enthusiasts often are at their most obnoxious about giving advice on how to drink wine. There are three basic factors to examining a wine: looking at the color, swirling it in the glass and smelling the bouquet, and taking a sip. Look at the color for signs of age and to note how widely varied the colors are for different grapes and different wine styles. But remember: darker does not mean better. It is mostly an indicator of age and grape type.

Smell the wine to ensure there are no warning signs of cork taint (that musty aroma), as well as to get an idea of what the wine will taste like. Almost all our ability to taste comes from the olfactory. So inhale, then take a sip. It’s what you’ve been doing your whole life when it comes to drinking. Go with what works for you.

There is a terrific three-part tasting method printed in Gourmet magazine decades ago. After your initial look at the wine’s color — done by holding it toward white light or against a surface that is as nearly white as possible — and first sniff (which doesn’t have to be over-dramatized like Miles in Sideways; just a good, regular sniff), take a sip and work it around in your mouth. This doesn’t have to be loud or overt, either, like a child reaching the end of the soda he’s drunk through a straw. Just try to get the liquid to coat your tongue. Swallow. You’ll get an expanded array of flavors from the simple effort of holding the wine in your mouth for a few seconds.

Second step: take another sip, but this time just swallow it down. No coating your mouth. Just drink it on down. Final step: take one more sip, move the wine to the back of your tongue, then lean your head back and take the wine into the back of your throat. After you bring the wine to the back of your mouth, return your head upright and let the wine come to the back of your teeth. Inhale over your tongue. This will give the wine serious aeration. Swallow. This is the best way to get a total view of the flavors in the bottle. All the wine's flaws will be exposed, but all the good things will be amplified as well.

This three-step tasting method is pretty simple, once you have a little practice (particularly on that final sip), but it’s not pretentious. It allows you to taste the wine fully, and it is a terrific way to find out what types of flavors you like. You don’t need to do it on every glass. Most of the time you’ll probably just want to drink away, like normal. But this way you can bond a little more with the beverage.

Final thoughts

See, that’s not so hard? There aren’t rules, merely suggestions. In the end, the best way to experience wine is to drink it. The more you drink, the more your knowledge will expand, the keener your palate will become, and the less daunting the whole experience will feel.

You might have a final question about serving temperatures, which is something to consider. Serve red wine at room temperature, perhaps with ten to fifteen minutes in the fridge during those sweltering Houston summer months. White wine is fine at fridge temperature, same with rosés and champagnes. But you can experiment with this, too. Maybe put more of a chill on high-alcohol reds to dull some of the alcoholic burn on the back end. Maybe drink a white wine at room temperature to see if it really is as seamless as it seems to taste. The bottom line is, nobody has to drink the wine but you. Conventions are mere guidelines, but the ritual of drinking wine adds to the romantic notion of it. Personalize that ritual however you like — it’s all about pleasure and getting out of wine what you want from it.