Friday, January 4, 2013

20 Things Everyone Thinks About Houston Food (But Nobody Will Say)

1. Houston hasn't yet reached adolescence in its development as a food city.

Close your eyes and think about Houston restaurants ten years ago. What was hot and exciting? Don't remember? What were the hot openings? Who's left? Mark's, Da Marco, Tony's, Pappas Bros. Steakhouse, Brennan's, Hugo's, Backstreet Cafe? Yes. They truck along and do so brilliantly. The larger point is that Houston has barely begun to expand beyond a handful of establishments that are interesting. But it's easy to get carried away and think, "Houston has arrived!" If you think that, however, it'll be gone in a flash, and you'll have never gotten there. Transforming Houston into a really meaningful culinary destination will take a lot of time. Don't jump to the conclusion because it's way more fun to enjoy the ride. Think about it. Houston had maybe a dozen really notable restaurant openings last year. In the San Francisco area? They're talking about ten this month. It'll be fun to watch Houston grow into a city like that.

2. Money talks.

The big money being spent on dining out in Houston still flows from the expense account/oil and gas sector. Hipsters and fadists are on the cutting edge, but they generally don't have the means to sustain institutions or trends. There's a reason why certain restaurants stay in business. People vote with their wallets and, bottom line, this is something you can't forget. Eating out is fundamentally a consumer product, and those with the bucks can be king-makers. So it's important to have a big-tent theory of food and bring everyone into the flow so the city can sustain the best restaurants.

3. Institutions matter.

This notion is linked to everything on this list. Think of any great culinary city, and you can instantly name institutions, restaurants you can't imagine the city without. New York and Peter Luger Steakhouse or the Carnegie Deli. Paris with Taillevent and Latour d'Argent. They don't have to be the best places, necessarily. But they've been there and done that for a very long time, and by and large they do it well. That matters -- because you can't live on constant innovation alone. You need to find and embrace as a city the restaurants that will become reasons for people to visit. These are restaurants that become part of the city's fabric.

4. Houston does have good barbecue.

This is one of those things people like to fight about because the amount of contested ground is so slim. Barbecue is like Tex-Mex or hamburgers or pizza. It's something whose inherent qualities are so good that, even when it's mediocre, it's pretty darn good. Gatlin's is good. Goode Company is good. You don't have to drive into Lockhart to get a fix on some nice smoked meat. It's fun to talk about what's better or best. But with something as joyously delicious as barbecue, there's no reason to go apoplectic over comparatively small degrees of separation.

5. Houston needs more good "daily" restaurants to form a culinary backbone.

Restaurant across the city in 2012 were events. There was a proliferation of places that, over time, could become flagship restaurants of a great food city. But great food cities need infrastructure in the form of tasty, serviceable, and simple neighborhood restaurants. These places don't require a reservation. They aren't see-or-be-seen establishments. They aren't a big production. They're comfortable. They cultivate clientele. They make you feel at home, whether you come in for a glass of wine and an appetizer or stop in late for a night cap or dessert. In short, the city needs more places like Poscol.

6. Food trucks are nice, but they don't compete with restaurants.

There's some quality stuff coming off of food trucks. But, on the whole, food trucks are more like diners or dive bars than they are trend setters. Sure, there are exceptions to every rule, but it's instructive to look at how notable food trucks like the Eatsie Boys and Modular are turning to traditional restaurant models for long-term success. This isn't about city propane regulations or anything else. Food trucks are an inherently limited medium. Good Dog Hot Dogs and Bernie's Burger Bus are delicious, and it's great to see an increase in the number of places where you can find good food carefully prepared. There's a role for food trucks to play, but they're not a threat to the traditional restaurant -- they're a complement.

7. Houston's ethnic restaurants are some of the best in the United States.

This is possibly the least controversial statement here. The breadth and quality of Houston's ethnic restaurants, particularly with Asian cuisines, is astounding. Food has a remarkable quality of allowing you to travel while staying put, and Houston does an admirable job of this. Keep spreading the word.

8. Most people don't understand tasting menus.

The current "backlash" against tasting menus seems like manufactured drama, though a kernel of truth lurks there. That's because so many consumers and, more importantly, chefs don't understand what a tasting menu is all about. Tasting menus are the ultimate, novelistic test of chefs: Can they create a cohesive, meaningful narrative, skillfully executed over a set number of courses that fills up a diner to just the right level -- full but not overly so. Thoughtful tasting menus take you on a culinary journey; they aren't just a restaurant's greatest hits or a mish-mash of unrelated dishes. They have form. This is a common misunderstanding, and sloppy execution of tasting menus causes frustration and unfulfillment. But the highest culinary highs come from such menus, so it's worth learning about them and seeking out fine examples of them.

9. Da Marco, Mark's, and Tony's still define "fine dining" in Houston.

They're here. They're successful. They've done it for a long time. They might not always be on the cutting edge of innovation -- although the exceptionally talented Grant Gordon at Tony's contradicts that statement -- but they do it well, and they will keep doing it. These are important restaurants, and just because they aren't as trendy with the foodie crowd as they once were doesn't mean they're devoid of influence. This is the level the hot new restaurants of 2012 should aspire to become.

10. Underbelly does not tell the story of Houston food.

Underbelly is a terrific addition to the Houston food scene. Chris Shepherd is a fun chef who has admirable passion that normally translates to the plate. But Underbelly does not tell the story of Houston food, and more importantly it does not have to. To think that a single establishment could articulate the diversity found across this mammoth city is shooting for the impossible at best and arrogant at worst. If it were possible, it would mean our city's food scene is far too limited. It's not the job of one restaurant to encompass all of Houston, and no restaurant can do it.

11. Houston needs more good sommeliers.

Great restaurant cities have numerous restaurants that provide a complete dining experience. An important part of that experience is having a sommelier who can provide beverages that enhance every dish you eat. The best example in Houston of a complete sommelier who provides a 360-degree experience for his guests is Sean Beck at Backstreet Cafe and Hugo's. He's unpretentious yet knowledgeable. He stays in tune with the customer's taste. He knows his menus and wine lists backwards and forwards, so he can be sure his recommendations go with the food. There are always interesting and unexpected wines, thoughtfully chosen and not haphazardly selected for their esoteric qualities, on the list. This is what you would expect of any sommelier at a minimum, yet so rarely find in Houston. At the same time, he also has an obsession with ensuring guest experiences are as good as they can be. This is how valuable a good sommelier can be. Houston restaurants should take note.

12. Fawning over obscure drinks masks true and thorough knowledge of wine, beers, and spirits.

Forget piling a dozen sherries on your wine list. Forget trying to dazzle customers with wines you've never heard of but whose presence on the wine list are to show off what a geek you purport to be. Just as developing into a great restaurant city takes years of hard work and lots of sweat, so does becoming a sommelier or skilled mixologist. This doesn't happen overnight, and there's no substitute for the hard work that comes in gaining the depth of knowledge of Houston's great sommeliers like the crew on the floor at Pappas Bros. Steakhouse. There is great virtue in getting a handle on all the fundamentals before forging into the esoteric. Too frequently these days, however, Houston restaurants feature odd wines and beers and spirits simply because of their novelty, and it comes off as an attempt to cover up a lack of genuine knowledge. Booze is fun. Take the time to learn it in-depth and provide customers the best experience possible.

13. Service at restaurants needs drastic improvement.

Even in the best restaurants in Houston, you can't assume you'll receive skilled service. Walk into any very good restaurant, and you are quite likely to be the recipient of service foibles, such as food coming out incorrectly or at the wrong time or getting your meals while waiting on silverware. Like all things restaurant, cultivating a serious culture of service and staffing it with professionally minded individuals is a monumental task. But a world class restaurant city cannot fall down on something as important as service, and nothing spoils a good meal faster than crummy service.

14. Houston is at a precarious time in its restaurant growth.

Don't buy your own press. Don't live in a bubble. The way you achieve greatness is by constantly striving toward perfection that, in almost every instance, you will not achieve. Houston's food scene has shown a dangerous proclivity toward bullying those who criticize and buying its own self-created hype. That's not the thing to do. Be proud of what the city achieves, but always strive to be better. Houston is still but a glimmer on the national map. It's a growing glimmer, but one that could be gone in the blink of an eye without ceaseless dedication to improvement, learning, and creativity.

15. Houston is insecure about the status of its restaurant and food scene.

Keeping an insulated community, buying your own press, and having an immature reaction to criticism are hallmarks of insecurity. Remember when Houston hosted the Super Bowl? There were so many big showings of how great and cosmopolitan Houston was. Cities that are great and cosmopolitan don't have to go out of their way to tell you that. They're confident in it. Houston needs to learn that. The acceptance the city craves so much will come with hard work. The dining scene here isn't as exciting as San Francisco or New York. But it's more exciting than ever. Enjoy that and keep focused on reaching the point where it can play with the big boys.

16. Central Market is better than any farmers' market in town.

The proliferation of farmers' markets over the past five years is a great development, in particular because it has consumers focused on quality first. But the simple truth is that Houston and its surrounding area aren't an agricultural green belt like the Midwest or California, and it's a challenge to find really good quality ingredients. Central Market, however, provides a reliable source of very good produce and other ingredients. An important part of sourcing ingredients, for any cook, is finding products of consistent quality. This isn't to say farmers markets are bad. They're awesome. But Central Market is the most reliable source in town.

17. BYOB should be standard.

This transcends Houston, but great food cities embrace wine and beer as much as possible, and BYOB should be allowed at the discretion of every restaurant. It's an incentive for people to eat out more. Arguments that BYOB is a threat to restaurants that serve wine, beer, and spirits have no merit. Look no further than cities like New York, Chicago, and San Francisco. The sad thing is that Houston's and Texas's alcohol wholesale, retail, and distribution networks are near-monopolies that are bad for consumers, and this extends to the choices restaurant patrons find on most wine lists and in BYOB prohibitions.

18. A sustainable food scene cannot be based on trends or fads alone.

You see it if you follow the club scene -- Richmond strip to Midtown to Washington Avenue. Trendy restaurant-goers are the same. They hit the Next Big Thing in droves, then move on. Fads and trends are fickle by definition and are no way to build long-term success. At some point, Alinea in Chicago will not be considered avant-garde. There is a process of natural selection for restaurants, and at some point, you have to begin building a canon of bedrock institutions. Remember that Chumbawumba was popular once. The hope is for exciting new restaurants to open every year in Houston, but just because something is new does not mean it's better.

19. Longevity matters.

This is closely related to No. 18. Remember in April 2011 when the Houston Press pronounced Stella Sola, open about a year, a Heights "institution"? Yet, only a year later, Stella Sola closed with no fanfare or farewell party. Meanwhile, unheralded-but-delicious neighborhood joint Glass Wall across the street trucks along to packed crowds. Running a restaurant is a business, and regardless of how cool or fun or interesting what you're doing is, making it work is essential. So before pronouncing Oxheart or Uchi or Underbelly or The Pass the new standard-bearer of all things Houston food, remember to add "potential" in front of all that. Because it only matters if they can do it over time. This is one part of what makes places like Brennan's so important.

20. If it plays its cards right, Houston can become a nationally relevant, vibrant restaurant town for decades.

One of the great characteristics of Houston as a city is that it is swift to embrace success. You can make a name for yourself on your own merits here more easily than in other cities, and that's an admirable quality. As a result, having open arms is in some ways already inherent to Houston's culture. Fostering success and driving competition to push the good to very good and the very good to great are what will propel Houston to the next level. So much of the food and restaurant scene today is concerned with sustainability -- from green architecture to sources of ingredients. But another type of sustainability -- of talent, creativity, and a drive for success -- are essential for Houston to reach its full potential.

Thursday, October 18, 2012

Does every palate matter?

|

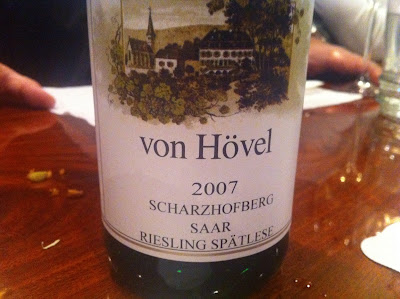

| What wines go off in your head like a light bulb? |

|

| Large-format bottles at Charlie Trotter's in Chicago. |

|

| Riesling at Lotus of Siam in Las Vegas is one of life's pure pleasures. |

Saturday, October 6, 2012

How much money is wine worth?

Before going further, however, a preliminary note: this isn't one of those screeds about "authentic" wine or excoriating those who pay a lot for bottles of wine. Those are traps. Terms like "authentic" and "a lot" are so relative, they have little fixed meaning. At the same time, the "worth" of wine isn't necessarily as simple as the cost of the grapes, oak barrels, bottles, labels, corks, etc. that go into making the wine.

So where does that leave the question: How much is that wine in your glass worth? Probably never more than about $50. At that point, other factors start playing havoc with the amount you pay. Chief among those are prestige and scarcity. That is easily enough understood. There are roughly 500 cases of Domaine de la Romanee Conti's Romanee Conti made each vintage, centuries of legend behind the wine, and tens of thousands of people who would gladly pay to drink perhaps the greatest trophy among all wines. Put that all together, and you can grab a 750-milliliter bottle of 2009 Romanee Conti for $10,000 if you're lucky (almost $400 per ounce).

So where does that leave the question: How much is that wine in your glass worth? Probably never more than about $50. At that point, other factors start playing havoc with the amount you pay. Chief among those are prestige and scarcity. That is easily enough understood. There are roughly 500 cases of Domaine de la Romanee Conti's Romanee Conti made each vintage, centuries of legend behind the wine, and tens of thousands of people who would gladly pay to drink perhaps the greatest trophy among all wines. Put that all together, and you can grab a 750-milliliter bottle of 2009 Romanee Conti for $10,000 if you're lucky (almost $400 per ounce).That's an extreme example, and the slope of prestige and scarcity that reaches its apex at Romanee Conti is much more difficult to discern at its earlier stages of incline. But here's an example you may have encountered: Have you ever drunk Santa Margherita Pinot Grigio? If you drink wine, you probably have tasted it. Six or seven years ago, it retailed for $15. Today, you're hard-pressed to find it for $20 or less. On a restaurant wine list, you might have found it for $25 to $30 in 2005. Today? Try more like $40 to $60. The wine hasn't changed. Its rapidly increasing popularity has. You're paying 30% more for the same wine. (Or, some may argue, lesser wine, as production of it has increased steadily over the years, too.)

In any case, it's not difficult to understand that prices increases with popularity. That's simple supply-and-demand. Pinot Noir prices in California jumped after the immense popularity of the movie Sideways. Popularity is only one factor in the price, but this doesn't tell us much about how much wine is worth.

The real bottom line here isn't existential or even complex. To determine what wine is worth to you, ask how much you are comfortable paying. It doesn't matter if you're willing to spend $5 or $10 or $20 for a bottle. Whatever fits in your budget and tastes good to you is what wine is worth. The larger point here is that more expensive isn't always better. You pay for a lot of things besides what's inside the bottle as prices increase. Today, there are more higher quality wine options across the board, which means there is even less reason to have label envy.

One final note: this shouldn't be taken as a condemnation of expensive wines or trophy bottles. Splurging can be fun. But wine connoisseurs have a terrible habit of making less sophisticated drinkers feel inferior or inadequate by showing contempt for less prestigious wines or those that have some esoteric point of interest. That can be intimidating, but it's a silly game to play. Not every occasion calls for a trophy bottle -- a hot day on the porch with a $10 bottle of Sauvignon Blanc is a recipe for a good time -- and just because a wine is rare and prestigious doesn't always mean it's the best. There are dozens of $100-plus Napa Valley Cabernets to prove this point.

There is nothing gained by drinking wine to impress others. You should drink for yourself.

You don't drink wine for the pleasure it gives others; you drink it for the pleasure it brings you. So the wine that fits your budget and makes you happy? However much it cost, that's how much a wine is worth.

Thursday, March 8, 2012

Houston, we have a problem ... with criticism

The sad thing is that Houston faces a serious threat to its ascent up the national food ladder. A startling number of those in the restaurant, bar, and beverage scene here apparently believe they are immune from criticism. Recently, newly opened Liberty Kitchen got in a flap with Alison Cook, the Houston Chronicle's long-time and well-respected food critic. (After Cook had been tossed, seemingly with provocation, by another restaurant owner in 2010.) Just a short time ago, Hubcap Grill's owner went ballistic over a tepid review from a Dallas critic, in a torrent of profanity and violent threats. Regardless of the subsequent apology, this sort of behavior makes Houston's restaurants come off as immature, petty, and, most important, unwilling to strive for the improvement that will allow them to shine on the national stage. And these incidents have not been relegated to professional critics.

Look no further than the lightning-rod of the Houston food community's ire -- Yelp -- and the vitriolic, out-of-hand dismissals of it to understand that Houston's restaurant scene, evolving each day, is in the midst of adolescence. And there is a lot of growing up to do still.

Before going further, however, all the Yelp critics can just take a deep breath. The point here is not to say Yelp is the end-all, be-all. Or that there aren't tons of unfair comments and reviews on Yelp. (Just go look at one-star reviews of the French Laundry to see preposterous unfairness.) It's important to realize the fundamental positive that Yelp represents. For the first time, the Internet and its accessibility affords restaurant owners, chefs, staffs, and anyone involved in the industry with an unprecedented reservoir of data. As with any significant amount of information, there will be outliers. In the realm of Yelp, these outliers are mean-spirited reviews of whatever ilk or sycophantic raves. There is worthwhile information in places like Yelp, even if it isn't written in the most articulate way, and this information isn't worthy of outright dismissal. The restaurant-going public is a massive, diverse body, and doubtless the Wisdom of Crowds applies to some extent. Recurring themes in reviews and feedback, regardless of the source, should make a restaurateur perk up his ears.

Granted, any sort of feedback open to the public, such as Yelp or Google reviews of the Chowhound board, provides unfiltered information. You'll run into various types of criticism, running the gamut from constructive to unwarranted, even malicious. It's serious work to filter through the feedback you get and determine what can make you better, but that is the nature of a service industry. It's a positive thing that the amount of information you receive from customers is at unprecedented levels. It's hard enough to just run an establishment, much less figure out how to improve it. Your customers are giving a torrent of information that is readily accessible. Why reject any avenue that might provide hints on how to get better?

Restaurants are humbling. That's the nature of putting yourself on the line, every day, in an endeavor as personal as food. In many ways it is like art or writing. But if you want to be the best -- or simply better than you are now -- how do you expect get there if you turn your back on people who care enough to tell you what worked and what didn't? As it stands right now, Houston's food community is defined by the largely (at least publicly) friendly relations among its members. But given how violently a surprising number in this community have reacted to criticism, one has to wonder whether Houston's ascendant food scene believes it is beyond reproach.

Naturally, it's good to see people have a positive attitude and build up one another, rather than fall victim to petty in-fighting and cynicism. Constructive criticism, though, is an essential part of a positive environment. Offering it means you care enough to want someone or something to get better. Being called names, shouted down, or shooed away as if you don't know anything gives a clear sign not that a reviewer was unfair but that an establishment is too scared to improve or more interested in resting on its laurels.

If you close off to constructive criticism and only respond to positive reviews or feedback, the only thing you have to rely on to reach that elite level of restaurant greatness is your internal drive. It goes without saying how few people can achieve greatness alone. What's worse, though, is that a dismissive attitude like that shuns the larger group that wants to see you succeed. It also creates an us-versus-them mentality that runs contrary to the collaborative spirit cultivated among so many in Houston's industry.

At the same time, there is the difficult problem of dealing with unwarranted and malicious criticism or even outright lies. As said previously, restaurants are a service industry. Interactions with customers, regardless of how wrong they may be, must be handled with decorum. Show fundamental respect and be professional. Don't let emotions dictate your response, no matter how tempting social media might make it. Handling obstreperous customers with tact will always earn you more points with the restaurant-going public.

Elevating Houston as a culinary destination is a collaborative effort. And that effort extends to patrons, regardless of the venue in which they voice their opinions and regardless of whether they are articulate or knowledgeable enough to be considered "foodies." Customers who take the time to come out for a meal or drink speak with the most important voice: their wallets. That's worthy of respect, just as the passion, time, and creativity those in the industry is worthy of appreciation.

Friday, December 9, 2011

A beginner's guide to flawed wines

But brett is, without a doubt, a bacteria that can destroy wine. Perhaps you have a threshold for enjoying brett, which is most often found in red wines; perhaps you are as intolerant to it as you should be of cork taint. If a wine is too full of brett for you? Send it back.

Thursday, August 4, 2011

Houston Restaurant Weeks: More than just food

From a food standpoint, the benefits are obvious. Chefs get to show off their ability to craft cohesive menus -- something that's too rare in Houston, even if only for three or four courses. A restaurant also gets the chance to showcase its food to parades of new customers with limited risk. The set menus are designed for easy success; they're short and sweet and ought to be easy for a professional kitchen to crank out consistently. HRW has the hallmark of a golden opportunity to expand the customer base of Houston restaurants for the long-term.

As a result, the hemming-and-hawing about HRW is head-scratching. Recent debates online have focused on whether HRW customers deserve the same level of service as those ordering off the regular menu or whether it's valid to base a Yelp review on a HRW visit. That's the wrong discussion. There is nothing to be gained in knocking an event that brings new customers in the door and, therefore, creates an opportunity for a restaurant to show its best.

What better way to educate than with showing off how complete the restaurant experience can be? Houston has been full of craft beer and cocktails dinners in recent months, but only a handful of restaurants have bothered to devise beverage pairings with their HRW menus. This is a missed opportunity to showcase an imperative skill for restaurants and their staffs: to come up with wine, beer, and cocktail pairings that enhance and elevate their food. Hugo's and Backstreet Cafe have come up with menus where complementary beverages are an integral part, no surprise given the deft skill of sommelier Sean Beck in elevating food by finding the right drink to go with it. Mockingbird Bistro and the Glass Wall, along with too few others, also offer thoughtful pairings with their HRW offerings.

The bottom line, simply put, is this: Restaurants in Houston offer more than just food. They offer an experience, an escape from your own kitchen, and a chance to enjoy one of the most exciting restaurant scenes in the country. In the first tier of restaurant cities in the United States -- New York, San Francisco, Chicago -- part of the joy is that you bask in the escape of the full dining experience, of which food is only one (very important) part.

Sunday, July 3, 2011

Lessons from Paris

1. Seasonal still rules the day, from Michelin Three Stars to bistros

Paris in April? Prepare for showers of morels and asparagus. But the refreshing thing is how deeply entrenched seasonal eating is in this culture. Restaurants don't trumpet the fact that they're serving what's local and of-the-moment. It's understood. This is the level of food appreciation -- an innate devotion to the freshest and best -- that has defined French food since the time of Marie-Antoine Careme and even earlier. (For a terrific discussion of this subject, and generally good writing on an array of topics, consult Mike Steinberger's excellent book Au Revoir to All That and his blog.)

This dedication to seasonality and freshness is the foundation of an admirable respect the French have for their food and the act of dining. And it is this fundamental and powerful building block that arguably is France's greatest culinary export right now. Take, for example, the two dishes pictured below. First, a glorious salad of fresh morels and asparagus from Le Bristol, the stunning three-star Michelin restaurant on the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré. It is a testament to seasonality, the finest ingredients, and artistic presentation.

Second, an equally delicious and seasonal preparation of morels, this time from the superb Bistrot Paul Bert. It's nothing more than fried eggs with morels and mushroom cream. Simplicity on a plate, yet providing a depth of flavor that, without supreme freshness of ingredients, would come across as heavy and plodding. Seasonal cooking doesn't only allow a chef to honor place and freshness; the right ingredients at the appropriate time inform the texture and weight of dishes.

2. It's about technique, not gimmicks

Look back at those stunning fried eggs from Bistrot Paul Bert above. It's all well and good to have the best ingredients, but they won't be worth a damn if you can't cook them properly. To cook simply and to showcase your ingredients is a risky proposition because, without expert technique, the food doesn't stand a chance. One striking thing about restaurants in Paris is their unwavering adherence to technique. You expect and demand perfect execution of basic preparations in high-end restaurants like Le Bristol, but the high quality of technique across the board is impressive. Just because a dish may be humble doesn't mean it isn't worthy of respect that borders on reverence.

Take boeuf bourguignon, the king of peasant dishes (now that's a paradox). Shown here in a faultless preparation from Christian Constant's inviting Les Cocottes, there was notable care in crafting a pure sauce that spoke of the beef without being tarted up with any gimmicks. The meat was cooked to that easy-to-know but hard-to-reach point of being fall-apart tender without the chuck toughening up again. Too often, simple dishes like this come out with tough meat, as if the cook has assumed he could braise it indefinitely without fault. Or by needlessly cooking the beef sous vide for days to make a splash by writing "72-hour boeuf bourguignon" on the menu -- there are places for advanced techniques, but they aren't always necessary.

Another good example of the triumph of technique over gimmicks comes from Chef Jean Louis Nomicos, whose Les Tablettes recently opened in the 16th arrondissement. This appetizer course has several moving parts: a glorious mushroom puree that relies on just a hint of richness that doesn't interfere with its pure flavor, perfectly sauteed white asparagus, freshest morels, and gloriously crisp sweetbreads.

3. A meal is an opportunity to be exploited, not an obstacle to overcome

Meals are a great social occasion. You can spend twelve hours at the office, but at least do yourself the favor of, once a day, sitting down to a proper meal to reconnect with friends or family. Shoveling in a bowl of pasta or wolfing down a 24-ounce steak to refuel the system isn't living anymore than eating a sandwich standing up. Take a moment. Have a pan-seared filet mignon with a slice of lightly sauteed foie gras on top and savor the people around you. You don't have to geek out about the food. Use the food as a vehicle to connect with those you love and your own life.

4. Like writing, food needs editing

More to the point, if you are cooking with the best ingredients, they need very little to bring out their finest qualities. Bistrot Paul Bert again serves as a fine example, with the roasted root vegetables and braised beef cheek with bearnaise pictured below. Basic, even humble, ingredients cooked with fine technique. You rarely need more ... well, maybe some wine.

5. Humble wine is just fine

The American wine press always seems to be abuzz about the next "cult" wine from California or futures prices of increasingly out-of-reach classed growth Bordeaux. There is talk about value, but it's surprising how few true value wines come out of California. When is the last time you had a meaningfully good wine for $10 that was produced domestically? It tends to be the exception rather than the rule. There's Two Buck Chuck and Gallo plonk that predominates supermarkets. But why isn't there something the equivalent of French vin de pays coming out of American wine regions? Even reasonably good, less expensive wines on Houston wine lists tend to be from Spain, New Zealand, and Italy.

There is a beautiful sense of security about wine consumption that the French have on a daily basis. Wine is part of setting the table, like a knife and fork, a social lubricant and celebration all in one.

Wednesday, June 29, 2011

Wine of the Moment: Numanthia Termes

Spanish wines can be hit or miss. You definitely get a lot of value in them -- particularly the whites, such as Albarino and Verdeho. But often the reds shoot too high and miss, like a cheap California Cabernet. One of the most standout wines of Spain's new school, missing all the pratfalls of the heavily oaked, high extraction crowd is the Numanthia Termes. Current release is 2008, and it's a steal at $24 or so. You can find it at Spec's quite readily and, also most of the time, at Central Market in the Houston area. It's a wine that gives a bit of a nod to Russian River Valley Zinfandel: pretty, spicy fruit flavors with ramped up acidity and noticeable tannic structure. It will satisfy those who crave nice fruit and the drying sensation you get from the young Cabernets that are so popular yet so heavy for Houston's brutal summer.

Termes is aged in once-used oak barrels, meaning there is less toast and vanilla for the wood to impart on the wine. The result is a surprisingly fresh, vibrant red that stands up well to the grilled red meat and barbecue that comes across summertime tables. Have at it.

Wednesday, April 6, 2011

What will be the ultimate legacy of the "local" food movement?

Obviously, there are a number of threshold questions to overcome in order to begin this discussion. First and foremost, how do you define "local"? Is it a 10-mile radius? 25? 50? More? Until the Industrial Revolution, this was easier to answer. Modes of transportation were much more restrictive, forcing food to come from relatively nearby. Railroads and airplanes have changed all that. Now you can get organic asparagus year-round, either from a farm down the road, California, or Peru.

But there are larger questions at hand, too. Is food sourced from a local source necessarily good simply by being local? What if you live somewhere without the possibility of thriving local agriculture; are you left out of the local movement entirely? How will "local food" evolve and sustain itself? In essence, what will the lasting impact of this local emphasis be?

It is that last question that holds the most interest. Fundamentally, the "local" movement, in part, is chasing a myth. It isn't practical -- perhaps, isn't even possible -- to return the United States to an agrarian ideal. That Jeffersonian moment has passed. So what, ultimately, will this movement become? This question is worth exploring because the local food movement has genuine value and will leave a meaningful impact on the way this country eats.

At some point down the road, looking back on what started as a revitalization of boutique food sources, these times will mark the true beginning of when Americans started truly caring about what they eat. For most of the twentieth century, culinary history in the United States was marked by technological advances: frozen foods, the microwave oven, fast food, ways to engineer "natural" flavorings, and other things that were meant to make eating easier. The problem with emphasizing technology in this way was that it resulted in the consumption of unhealthy, poor quality food. Instead of enjoying meals, they became obstacles to be overcome, met and discarded in the fastest, cheapest way possible. That results in a lot of issues, including creating a culture that doesn't value the food it consumes -- an odd situation when food, when it comes down to it, is the fuel to make our bodies go.

This lack of appreciation for food -- taking the easy way out -- has offered the local movement its greatest opportunity and in which lies its greatest hope. Eating well is not something for "foodies." It is not something for the rich. It is not something for the person who saves just to experience one meal at the French Laundry. It is for anyone who's willing to embrace it. Good food takes care and attention, which are two things that precisely are hamstrung by the prevalence of technological food, with its dinosaur-shaped chicken nuggets.

How does the local movement become the savior, pulling the country out of its grease-laden, deep fried, engineered obsession with packaged food? For starters, locavores care about what they eat. That is not a hallmark of technology foods, to put it mildly. With reflection, this desire to do well with good ingredients is the logical progression from Julia Child's grand (and deserved) legacy. Julia frequently preached doing better with what you have -- even if you had to use frozen spinach or come up with a substitute for French flour. Locavores, more so than foodies as a class, do not tolerate compromise. They are specific and passionate in their desire to acquire the best ingredients available.

At this point, you could run into road blocks. What if the best ingredient isn't available locally? Do you really have to stay within a 5-mile radius? Ten? More? To a certain extent, those issues are semantics. It's about what "local" means to you. But this emphasis on quality ingredients and caring about food are the the true heart of the local movement. It is about finding the best ingredients from people who are passionate and skilled. There's no need to go furtherthan that. The essential step is eating well and putting love and attention on your food. This is about rejecting the technology food culture that has given us blue raspberry flavoring, cheese in a can, and Kraft avocado-free guacamole.

Doing so pushes American food culture in a better direction, largely rejecting a look-what-we-can-do infatuation with technology (molecular gastronomy saved for another time) and toward an emphasis on quality and good food. Regardless of anything else, this is a genuine revolution and may determine the most significant legacy of the local food movement -- and a glorious one it would be. A country that embraces meals as an opportunity to be exploited, to bring people together on a daily basis and not just at Thanksgiving or Sunday supper? That is worth striving for.

Wednesday, February 2, 2011

Wine every day, part three

Hopefully by now you think wine is something you want to try. But a basic task remains: how do you drink it? That’s a stupid thing to ask, isn’t it? Open up and swallow it down. Well, it’s not quite that simple if you want to maximize the enjoyment of this wonderfully layered and complex beverage, but it doesn't have to be overly complex, either. Tony Soprano put it right during season five of The Sopranos when, after he uncorked a bottle of Dom Perignon to celebrate reconciling with Carmella, he scolded Anthony Junior for gulping it down like beer. “You gotta savor it,” he said. One thing that makes drinking wine such a pleasure, as with many things we enjoy in our lives, is the ritual that surrounds it. By no means should the ritual subordinate the actual pleasure of swilling it down, but a few small steps can maximize the experience.

Opening the bottle

You’ve done this before, but there are a couple tips to remember. First, your corkscrew makes a difference. Much like wine itself, they come in a lot of varieties, from the cheap to the ostentatiously expensive. The basic styles include the waiter’s corkscrew. These can be a challenge if you don’t have a lot of experience, since they don’t always go straight into the cork. There is also the “drill” type, which covers the top of the bottle and screws into the cork while a pair of arms raise into the air. Push the arms down, and the cork comes out. This is a great corkscrew, but make sure you get one where the tip that goes into the cork first is straight, not curved, or you can have the same problem as with the waiter’s corkscrew.

The easiest entry-level corkscrew to use is a Screw Pull. It’s also sometimes called a “rabbit” style wine opener. A good one will run you about $100, but it makes opening wine — young and old bottles — a breeze. You can also get a solid one for $20, but expect to replace it in a year or two.

Once the bottle’s open, do this: Smell the cork. A lot of people dismiss this as pretentious and unnecessary, a relic of past, unenlightened times — just the sort of thing it’s important to guard against. But the critics are dead wrong. Smell the cork. If it smells musty or like wet socks or mold, it is the first indicator that your bottle might have “cork taint,” which is what winos say when a chemical compound known as TCA, found in corks, ruins a wine. There are degrees of cork taint, and the cork is the first place where the off aromas will show up. Consider it the wine bottle's canary.

Last, pour a small amount of wine into your glass and take a taste. The wine may well need to have more contact with the air (called “opening up” or “aerating”) to fully develop its aromas and flavors, but the initial sip will let you know if the wine is flawed.

What kind of glass?

The key word here is “glass.” Fundamentally, you don’t need to worry about anything else other than drinking your wine out of a real glass. It doesn’t matter what shape it is. It’s just important not to be drinking out of plastic. You’re not going to basement keg parties anymore. (At least not to drink wine.) Down the road, you’ll want to invest in some inexpensive but good wine glasses. Target carries an excellent line of reasonably priced Riedel glasses. You should certainly consider three varieties: one for red wine, one for white wine, and a flute for champagne.

You want wine glasses to be clear — no color at all, without etching or cut glass. You want the lip of the glass to be thin, not thick and clumsy, which will negatively affect how you taste the wine. Other considerations change depending on the type of glass. For example, for red wines, use a large glass with a wide bowl. This allows you to swirl the wine in your glass and aerate it, making for a more aromatic bouquet (as winos call the aromas). For white wines, the glass is similar but smaller, without quite as large a bowl. Champagne flutes are probably old hat. But when you pick one out, simulate taking a sip to see if the tip of your nose hits the side of the glass. Many flutes these days are made with too narrow an opening on top, and if your nose makes contact, the oil will come off your skin, and that will inhibit the bubbles. What fun is champagne with no bubbles?

Pouring

This isn’t hard, but promise to keep one thing in mind: Don’t pour too much wine into each glass! Two or three ounces are plenty. This allows you to enjoy the wine and see how it develops as it has increasing contact with air. Many restaurants, if a party of four orders a bottle of wine, will empty it in one round of pours. What good is that? Pour in moderation, please. It’ll still be left in the bottle.

Drink up … but be sure to sniff first

Let’s be frank. Wine enthusiasts often are at their most obnoxious about giving advice on how to drink wine. There are three basic factors to examining a wine: looking at the color, swirling it in the glass and smelling the bouquet, and taking a sip. Look at the color for signs of age and to note how widely varied the colors are for different grapes and different wine styles. But remember: darker does not mean better. It is mostly an indicator of age and grape type.

Smell the wine to ensure there are no warning signs of cork taint (that musty aroma), as well as to get an idea of what the wine will taste like. Almost all our ability to taste comes from the olfactory. So inhale, then take a sip. It’s what you’ve been doing your whole life when it comes to drinking. Go with what works for you.

There is a terrific three-part tasting method printed in Gourmet magazine decades ago. After your initial look at the wine’s color — done by holding it toward white light or against a surface that is as nearly white as possible — and first sniff (which doesn’t have to be over-dramatized like Miles in Sideways; just a good, regular sniff), take a sip and work it around in your mouth. This doesn’t have to be loud or overt, either, like a child reaching the end of the soda he’s drunk through a straw. Just try to get the liquid to coat your tongue. Swallow. You’ll get an expanded array of flavors from the simple effort of holding the wine in your mouth for a few seconds.

Second step: take another sip, but this time just swallow it down. No coating your mouth. Just drink it on down. Final step: take one more sip, move the wine to the back of your tongue, then lean your head back and take the wine into the back of your throat. After you bring the wine to the back of your mouth, return your head upright and let the wine come to the back of your teeth. Inhale over your tongue. This will give the wine serious aeration. Swallow. This is the best way to get a total view of the flavors in the bottle. All the wine's flaws will be exposed, but all the good things will be amplified as well.

This three-step tasting method is pretty simple, once you have a little practice (particularly on that final sip), but it’s not pretentious. It allows you to taste the wine fully, and it is a terrific way to find out what types of flavors you like. You don’t need to do it on every glass. Most of the time you’ll probably just want to drink away, like normal. But this way you can bond a little more with the beverage.

Final thoughts

See, that’s not so hard? There aren’t rules, merely suggestions. In the end, the best way to experience wine is to drink it. The more you drink, the more your knowledge will expand, the keener your palate will become, and the less daunting the whole experience will feel.

You might have a final question about serving temperatures, which is something to consider. Serve red wine at room temperature, perhaps with ten to fifteen minutes in the fridge during those sweltering Houston summer months. White wine is fine at fridge temperature, same with rosés and champagnes. But you can experiment with this, too. Maybe put more of a chill on high-alcohol reds to dull some of the alcoholic burn on the back end. Maybe drink a white wine at room temperature to see if it really is as seamless as it seems to taste. The bottom line is, nobody has to drink the wine but you. Conventions are mere guidelines, but the ritual of drinking wine adds to the romantic notion of it. Personalize that ritual however you like — it’s all about pleasure and getting out of wine what you want from it.